Šíma, Orwell, Camus, Malraux, de Gaulle, Mauriac, Maritain, Misia Sert, Picasso, Nabokov, Lesier… these are just some of the names associated with the personality of the Polish painter Jozef Czapski, who spent more than fifty years of his life in France, thirteen years in free Poland, and who was born in Prague.

He was a Polish painter, illustrator, writer, essayist, critic, soldier, and survivor of internment in the Soviet camps in 1941.

He was born in Prague in 1896, and he died in 1993 in Le Mesnil-le-Roi, France, and was also buried there in the local cemetery.

He spent his childhood on the family estate in today’s Belarus, which was at that time (1896–1918) divided Polish territory under Russian occupation. His father was Polish, his mother Austrian. He came from a family of counts, but he never used his noble title.

He was educated in Russian schools in St Petersburg and studied at the Faculty of Law. After the Bolshevik Revolution he settled in liberated Poland, living in Warsaw and Krakow, for his family’s estates were stolen by the Bolsheviks. He also lost his family seat in Przyłuki as a result.

He also studied briefly at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, then from 1921 he continued his education in Krakow in the studio of Professor Józef Pankiewicz, who also spent a long time in France and was a friend of Pierre Bonnard.

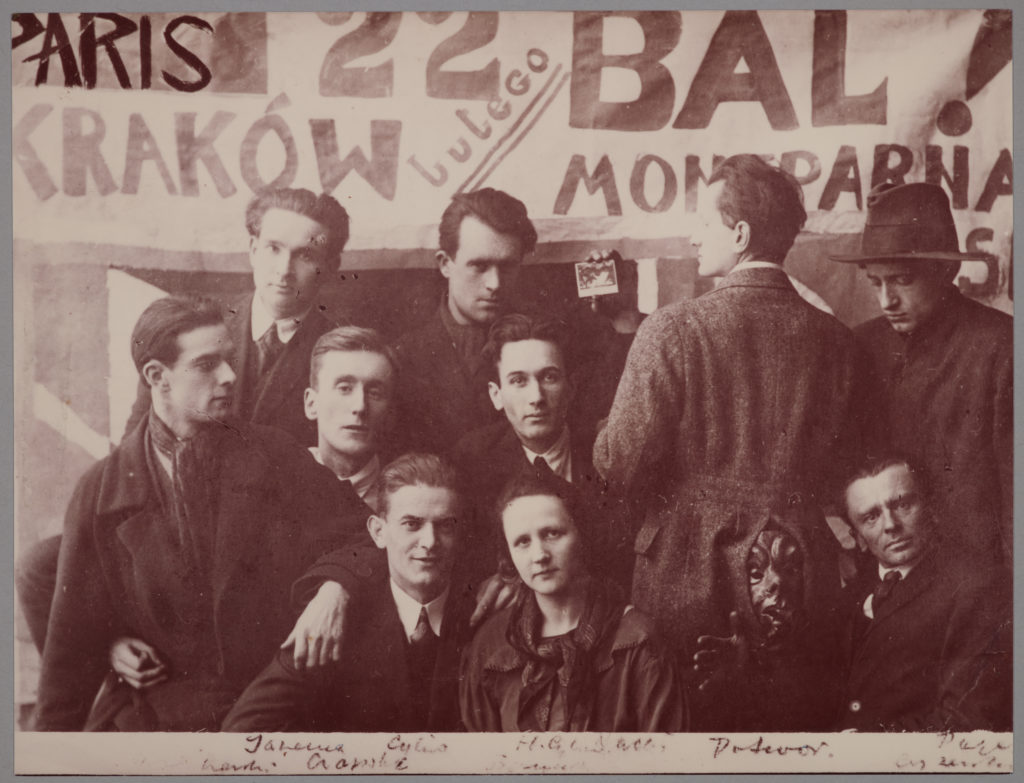

In 1923, Czapski and his friends founded an art group called Kapiści (the Kapists), and in 1924 he went to Paris with them, visiting art galleries, attending Russian ballets, and devouring new artistic trends, but also working as an illustrator for fashion magazines. He met many important intellectuals during this time, such as André Malraux, François Mauriac, and Jacques Maritain. He discovered the work of Marcel Proust. He presented his paintings for the first time in a Kapist group exhibition at the Zak Gallery in Paris. He regularly visited Misia Sert in her flat on the Rue Constantine. She was the muse of Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Félix Vallotton, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard, but also an inspiration for many writers such as Proust, Cocteau, Mallarmé, and Apollinaire. She was also a friend of the composers Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, and Karol Szymanowski and she decided to help the Kapists. Thanks to her, Czapski became acquainted with prominent cultural figures such as Jean Cocteau, Sergei Diaghilev and his dancers Nijinsky, Balanchine, and Lifar. His close friend Daniel Halévy would tell him stories about Degas.

Between 1924 and 1925, the Polish painter often stayed in France, but after the Second World War, when he managed to escape from the Soviet camps, he was unable to return to Poland, which had become Communist. His name was on the list of undesirables.

He stayed in France and settled first in Paris and later in Maisons-Laffitte, at 1 Avenue Corneille, before moving permanently in 1954 to house number 91 in Avenue de Poissy in Le Mesnil-le-Roi – also the location of the Instytut Literacki publishing house, which operated from exile.

His small bedroom at no. 91 doubled as his studio. He was fascinated by the paintings of Cézanne and van Gogh, and he loved Pierre Bonnard. He considered Chaïm Soutine, Nicolas de Stäel, and Max Beckmann the masters of artistic expression. But he also appreciated many others. The list would be too long.

For more than fifty years he walked the streets of France, sketching and painting. He observed the daily life of Paris. In his paintings we can see the Salle de Pleyell, theatres (such as the Odeon), but also actors and actresses he knew and who commissioned paintings from him – for example Madeleine Renaud or Pierre Viallet… Drawings have been preserved of Michael Lonsdale, whom he saw in a production of Witkacy’s Mother. His notebooks, of which more than 270 have survived in the archive, include portraits of George Orwell, Edith Piaf, General Charles de Gaulle, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, André Malraux, and many other world-famous figures.

He met André Malraux in the 1930s at Daniel Halévy’s. The author of La Condition humaine (The Human Condition) bought Czapski’s paintings after the war, when he was Minister of Culture. Thanks to him, the Polish artist got to know a number of French diplomats and government officials who helped Poles when the Communists came to power in their country after the Second World War.

Czapski’s paintings and drawings can be found in many private and public collections in the Czech Republic, Great Britain, Poland, France, Switzerland, Canada, Japan, the United States, Belgium, Germany, and in South America.

Let us highlight here the private collection of Gilles de Boisgelin, which includes more than twenty-three works of art, and can still be seen today in the beautiful Kurozwęki Palace. This French diplomat married a Polish woman, Jolanta née Wańkowicz, the daughter of a Polish diplomat. It was thanks to his friendship with Czapski that he entertained many Poles in his home and also supported them.

Let us explore bars, cafés, restaurants, and concert halls through Czapski’s paintings; let us see various places through his eyes. He was sensitive to the plights of people and often stopped in unusual corners of the city to capture the life of the poor and destitute, the life of the street… He was captivated by the faces of old women, in whom he saw the hardship of life.

Following Cézanne, he liked to paint the nature that surrounded him. In his paintings he depicted seascapes on the shore, fields, country roads, but also animals. Like his master Paul Cézanne, he would immerse himself, and lose himself, in nature.

He was fascinated by Dutch painting and honed his still-life skills, which in turn helped craftsmanship; he worked on the hand-and-eye connection, waiting for inspiration, a vision…

Texts by Elżbieta Skoczek